The lost Battle!

Introduction:

The Fairey Battle is most remembered for its heavy losses during the first phase of the second world war and for the inadequate results it achieved with its missions. This was, however, not the fault of the type! The basic design was very sound at the time it was generated and at its operational introduction it was one of the most modern aircraft of the world. A rapid development in the fighter from a 200 mph biplane to a 350+ mph monoplane in the few years after the Battle went operational was one of the main reasons for its operational failure at war. At the outbreak of the war the Battle was not only already obsolete, but also lack of fighter cover and inadequate armament and armour were a direct cause of its heavy losses. The losses may be further explained by the type of missions it had to fly: low level bombing missions on targets heavily defended by anti-aircraft guns. In this article, we will have a closer look at this interesting type.

(Collection Loet Kuipers)

Design and early test flights:

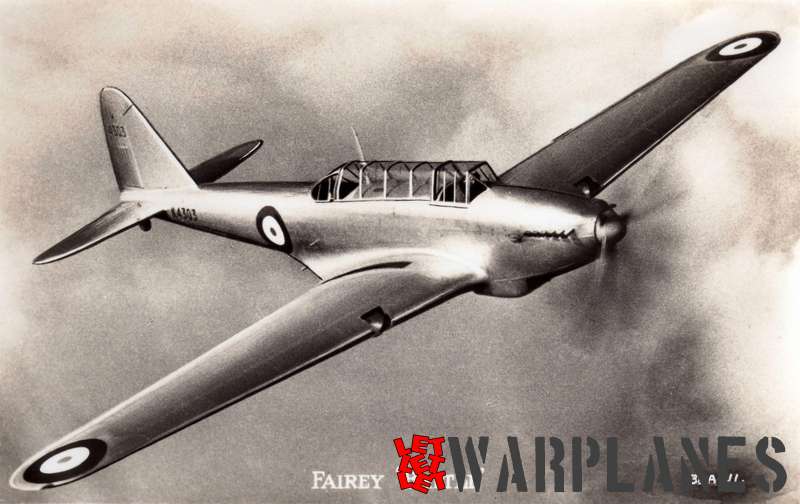

In August 1932 the British government released Specification P.27/32 for a replacement of the then operational Hawker Hart and Hind light day-bomber biplanes. It called for a single engine day bomber with a maximum empty weight of 6300 lbs (2858 kg), a crew of two, a gun armament of one fixed and one movable machine gun, a bomb load of up to 1250 lbs (567 kg), a range of 600 miles (966 km) and a maximum speed of at least 195 mph at 10,000 ft (314 km/h at 3048 m). A number of aircraft manufacturers submitted a design proposal, but at the end only Fairey and Armstrong Whithworth received a contract for a prototype. Fairey’s proposal was a low wing monoplane with a Rolls Royce Merlin engine and a single ‘greenhouse’ two seat cockpit; named ‘Battle’. Armstrong Whitworth built their P.27/32 bomber as the A.W.29. The Battle prototype K4303 made its first flight on 10 March 1936; the Armstrong Whitworth A.W.29 K4299 followed on 6 December of that year. Main difference with the Battle was its engine; a 870 hp Armstrong Siddeley Tiger radial air cooled engine while the Battle was fitted with the new Rolls Royce Merlin liquid cooled engine. During comparative trials the Battle was found to be vastly superior and the A.W.29 was rejected. Early flight testing of the Battle was without big problems and it was proudly shown on 27 June 1936 at the big RAF flight display at Hendon and some time later at the SBAC airshow as Britain’s new ‘wonder-weapon’. To replace its ageing fleet of biplanes the RAF placed a preliminary order for 155 Battle Mk.I’s (serial nos. K7558-K7712) in May 1936.

Into production:

Production of the Battle order started at the Fairey Stockport plant and the order was to be completed in June 1937. However, by that time only 84 had been delivered and with new orders placed a ‘shadow factory’ was set up at the Austin Motor works at Longbridge. Production started here in 1938, although also initially at a slow rate.

Over the next years the following numbers of Battles were produced:

Fairey Austin total

1937 81 – 81

1938 352 28 380

1939 513 524 1037

1940 218 480 698

Total production batches of the various Battle versions were as follows:

K4303 prototype to A.M. Spec. P.27/32 and 23/55 (1)

K7558-K7712 (155) built at Fairey Stockport

K9176-K9220 (45) built at Fairey Stockport

K9221-9486 (266) Fairey production; K9487-K9675 cancelled

L4935-L5797 (863) built by Austin Motor Company

N2020-N2066; N2082-N2131: N2147-N2190; N2211-N2258 (189) Fairey production

No. 58-73 (16) Supplied directly to to Belgian Air Force; Fairey production -no RAF serial no. given

P2155-P2204; P2233-P2278; P2300-P2336; P2353-P2369 (150) Fairey production

P5228-P5252; P5270-P5294 (50) Fairey production

P6480-P6509; P6523-P6572; P6596-P6645; P6663-P6692; P6718-P6737; P6750-P6769 (200)

R3922-R3971; R3990-R4019; RR4035-R4054 (100) Austin Motor production

R7356-R7385; R7399-R7448; R7461-R7480 (100) Fairey production; all trainers

V1201-V1250; V1265-V1280 (66) Austin Motor production. 234 of same order cancelled.

Total production: 2201

The Battle production was ended in November 1940.

Foreign users of the Battle were:

Belgium: 16 Battle 1’s were delivered in 1938 from the Fairey Stockport production line. They were all lost or damaged during the German invasion in May 1940. They carried the registration nos.

58-73.

Turkey: between August and November 1939 29 Battled 1’s were exported to Turkey. In May 1940 an additional target tug Battle was exported

Greece: in December 1939 11 Battle 1’s were exported to Greece after an initial ban. They were used with some success against invading Italian forces in 1941, but when German troops invaded Greece the remaining machines were all destroyed.

Ireland: Battle target tug V1222 was an involuntary export when it landed after a training mission by accident in Waterford in Ireland. The Irish government impounded that machine for the Irish Air Corps where it served until 1946.

A great number of Battles was exported to other countries of the British Commonwealth. Canada received some 700 for training purposes. Australia received for the same use 365 Battles. South Africa had during the war 27 Battles on its inventory. Further Commonwealth users were Rhodesia ( 25), New Zealand (2) and India (4).

Battles into battle:

In the years before the war the Battle became operational at a large number of R.A.F. squadrons. They not only replaced older biplane type light bombers, but also went to various training units. When the war broke out, a substantial number of Battles (around 160) were stationed in France at the British Advanced Air Striking Force.

(Collection Loet Kuipers)

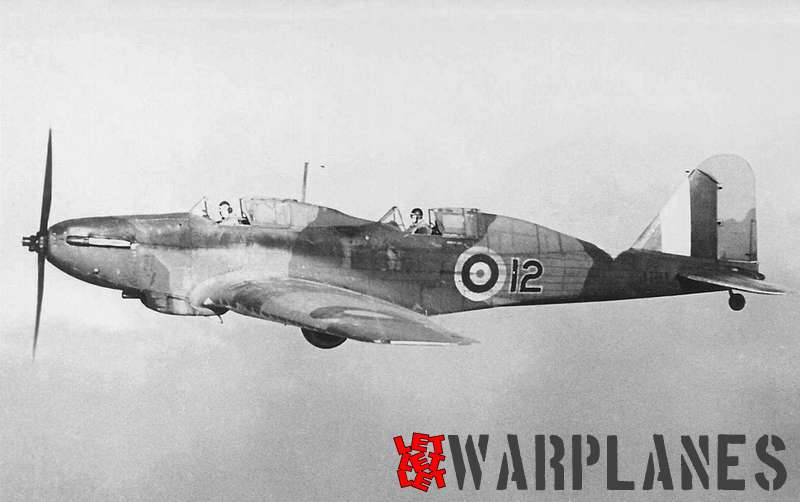

They were the first to fight against the invading German forces in France with daylight missions against selected targets like bridges. They flew their missions mostly without a fighter escort and had to pay a heavy price. In spite of this, the first aerial combat victory made against the Luftwaffe was with a Battle when it shot down a Messerschmitt Me-109 on 20 September 1939. However, during the daylight missions the Battles suffered very heavy losses. When Battles flew a mission against German troops in Luxemburg on 10 May 1940, 13 out of a group of 32 were shot down. Also on other occasions losses were very high. Fl./O Garland and gunner Sgt. Gray earned posthumously the first Victoria Cross when they failed to return from a mission against a bridge in Belgium. On another mission to attack bridges only 28 Battles returned from a group of 63.

(Collection Loet Kuipers)

When no. 12 sq attacked the Meuse bridge at Maastricht in the Netherlands in May 1940 all 5 Battles used for this mission were shot down. The conclusion that the Battle was totally unsuitable for this type of missions was quickly drawn and soon all Battles were withdrawn as first-line day bombers. The Battle soldiered on for a number of years as a training aircraft and as a target tug and many light bomber versions were eventually converted for this role. A number of Battles were fitted as a trainer with two separate cockpits. Others were used for gunnery training with a gun turret in the rear and a single place cockpit.

At this stage it carried no markings or colour scheme. Also this test bed had a fixed undercarriage.

(Collection Loet Kuipers)

Conclusion:

When the Fairey Battle flew for the first time on 10 March 1936 it definitely was one of the most modern light bombers in the world and with its Rolls Royce Merlin engine of more than 1000 hp and a maximum, speed of 415 km/h it was much faster than the biplane fighters then in service. However, when the Second World War broke out and the Battle was used for daylight sorties against enemy targets it was soon evident that it was in fact already obsolete and no match at all against the new generation of heavily armed fighters. Losses were so heavy that the type was soon withdrawn from frontline service, but in spite of this the Battle soldiered on in other roles like training and target towing. Basically there was nothing wrong with the Battle; it was very easy to fly and forgiving and could absorb a lot of punishment but this was not enough for its original role as a light bomber when the war broke out……

Experimental versions:

A small number of Battles was used for installation and testing of various kinds of new aero engines.

K9370 with an experimental 24 cyl. 2000 hp Fairey P.24 Prince engine

K9222 was a test bed for the experimental Rolls Royce 24 cyl. 1200 hp Exe engine

K9240 was fitted with a 995 hp Napier Dagger engine

K9278 and L5286 served as an engine test bed for the 2000 hp Napier Sabre engine

K9331 was fitted with a 14 cyl. Bristol Taurus radial engine of 1000 hp

N2042 and N2184 were used as engine test bed of the Bristol Hercules 14 cyl. radial engine of 1375 hp

Eight Battles (K7572, K9257, K9406, K9477, N2058, N2110, N2234 and P6752) were used as engine test beds for various versions of the Rolls Royce Merlin. One of these, N2234, was flown with a Merlin XII and a ‘chin’ radiator.

Other Battles were used for testing of constant speed propellers, glider towing, airborne radar, aerial mines and for flare towing experiments to illuminate target aircraft at night.

Contemporary types:

(Collection Loet Kuipers)

The contemporary type bearing the closest resemblance with the Fairey Battle was the Russian Ilyushin IL-2 Shturmovik, although this type flew much later. Retrospectively it is hard to say whether or not its design was influenced/inspired by the Fairey Battle, but basically it was the same ‘formula’ for an armed light bomber. The difference was that the Il-2 carried a much heavier armament. It was also much better armoured for the protection of the occupants, a thing that lacked completely on the Fairey Battle. Also the Il-2 was no match for enemy fighters, but its sheer numbers made this less relevant; although also the Shturmovik suffered heavy operational losses. It seemed the Russians had learned their lessons by studying the outcome of the operational use of the Fairey Battle!!

Remarks by Carlo Soliani: “Fairey Battle T.Mk.I in the livery of a Service Training Flying School of RCAF. The plane is painted in yellow with black, oblique stripes. In the book “The Hamlyn Concise Guide to British Aircraft of WW II” at page 96 there is a colour profile of a similar plane with the same livery and individual number (5). The caption tells: “Fairey Battle T.Mk.I of No. 8 Service Training Flying School, Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada, in mid-1943.”

Technical details (Battle Mk.1 bomber):

Power plant: Rolls Royce Merlin II liquid cooled 12 cylinder V-engine of 1030 hp

Dimensions:

-Length 12.90 m

-Wingspan 16.46 m

-Height 4.72 m

-Wing area 39.2 m2

Weights:

-Empty 3040 kg

-Loaded 4900 kg

Performances:

-Maximum speed 414 km/h at 6096 m

-Service ceiling 7620 m

-Range 1600 km at 4877 m and 322 km/h

Crew: Pilot and gunner/navigator

Armament:

-Guns one fixed .303 inch (7.92 mm) Browning machine gun in the right wing

one movable .303 inch (7.92 mm) Vickers ‘K’ Lewis gun in the rear cockpit

-Bombs fours 250 lbs (113.4 kg) bombs stored in pairs in internal bomb bays in the inner wings.

The Fairey P.4/34:

Both Fairey and Hawker submitted in 1934 design proposals for the new Specification P.4/34 two seat light bomber that was suitable for dive bombing, reconnaissance and as a fighter-bomber. The Fairey design used much from the Battle, but it was better streamlined with a sunken cockpit section and was somewhat smaller in dimensions. A prototype was built , with serial number K5099 making its first flight in January 1937. Eventually the Hawker design was selected, that became later known as the Henley. This was, however not yet the end of the Fairey project. It seemed to fulfil very well the specification O.8/38 for a two-seat naval fighter and became finally known as the Fulmar. It carried a heavy armament of not less than eight forward firing machine guns in the wings. It definitely was not on equal terms of contemporary single seat fighters, but it had a very long range and for long patrol missions over sea an extra navigator on board was quite a relief for the pilot! In total six hundred Fulmars were built.

(Irish AC photo)

Camouflage and markings:

The prototype had an all-over aluminium scheme. Production Battle Mk.1’s had a scheme of dark brown/dark green on the upper side and semi gloss black at the underside. Target tugs and trainers had more colourful yellow colour schemes.

The Belgian Battles had basically the same scheme as the R.A.F. Mk.1 Battles, but with Belgian national markings.

(Irish AC photo)

Tips for the model builder:

Airfix had a very nice 1/72 Battle Mk.1 in its old product range that is luckily still available. The early release from late fifties/early sixties had decals for No. 12 sq. Battle P2332 that attacked the Maastricht bridge and for a Belgian Battle with registration no. ’60’. For that time it was an excellent kit with very nice surface detailing and with wing bomb-bays that could be built in open or closed position. Such Airfix kits in the old style box must be regarded as collector pieces meanwhile, although it still can be found at aviation fairs for less than 10 Euro!

At 1/48 there is a nice limited production Battle Mk.1 from Classic airframes. Maybe the fit needs some correction and filling/sanding because this kit has no locating pins, but in general this will present no great problems to the model builders with some more experience.

Both kits are fully recommended!!

(Mick Gladwin collection)

Survivors:

At the moment there is no airworthy Fairey Battle, but some are kept in various aviation museums.

The Brussels Air Museum is currently restoring Fairey Battle R3950 from the Strathallan collection. It was acquired by the Belgian Ministry of Defence in exchange for a Spitfire Mk XIV. It is now partially restored in Belgian air force colours carrying registration no. 70.

Battle R7384 is on display in the Canadian National Aeronautical Collection at Rockliffe, Ottawa .

Battle N 2188 has been recovered from a swamp and is now being rebuilt at Port Adelaide, Australia.

Battle L5343 is on exhibition at the Royal Air Force Museum at Hendon, U.K. after an extensive rebuilt using parts of Battle L5340 that was partially destroyed by fire.

References:

-Bruce Robertson, British military aircraft serials 1911-1971(4th revised edition), Ian Allan UK (1971)

-Sidney Shail, The Battle file, Air Britain, UK (1997)

-H.A. Taylor, Fairey aircraft since 1915, Putnam UK (1974)

Books:

Sidney Shail’s book ‘The Fairey Battle File’ must be regarded as the most important and most complete reference work on the Fairey Battle and it is an absolute must for everybody with a special interest in this type. Basically all data on all Battles are given; including a number of colour pages with profiles of all versions. Also the operational missions flown by the Battle are given in detail. The book is still available at Air-Britain, U.K. at £20.- for Air-Britain members and £25.- for non-members.

The Twin-Battle:

Fairey already proposed a twin engine version of the Battle at an early stage (1933), but the Air Ministry was not interested and insisted on the construction of the original single engine prototype, ‘conform Spec. P.27/32 ‘.

In spite of this disinterest, Fairey made in 1937 a further proposal for a twin engine version, both with the experimental Fairey P16 engine and the Rolls Royce Merlin. Even the use of the Fairey P24 (a double P16) and the Napier Sabre, then in development, was considered. In 1938 Air Ministry was again interested in a twin engine fighter, but the type finally selected was the Bristol Beaufighter. If the original design from 1933 had been followed up instead of rejected, the R.A.F. might have had already in 1936 a twin engine Battle with performances similar to those of the Spitfire or the Hurricane. At the Battle of Britain, cannon-armed twin engine Battles would have played a very important role against incoming German bombers if they had been available!

All Photographs: Nico Braas/Letletlet-Warplanes collection unless stated otherwise.

Nico Braas

Not to nitpick, but in English it’s “cylinder”, not “cilinder”, although I believe that spelling is correct in some languages.

More importantly I disagree that the Il-2 has any relation to the Fairey Battle. They share nothing other than the same general layout, and it’s a very obvious, common-sense layout. You could say the Japanese Ki-51 Sonia is a “copy” of the Battle, other than having a radial engine and fixed gear. Heck, you could say the same, but even more accurately, about the B5N Kate, or even the B6N Jill. The B5N is a lightly-loaded monoplane with a three-man crew, 1,000-2,000lb bombload, 1,000hp-class engine. The bombardier sits in the middle and aims the bombs through a window in the floor (when not being used as a torpedo bomber). The B6N is the same, only bigger and more powerful. The Ki-51 is a light bomber and observation plane, with a 2-man crew and also can aim bombs through a window in the floor of the rear. The Ki-30 Cherry comes to mind. All of these are far more like the Battle than the Il-2…even the SBD and the TBD Devastator, really. Far from being unusual, the general layout is the FIRST thing that comes to mind when asked to design a light bomber. It’s only by thinking outside the box that you come up with twin engines, twin tails, machines like the Fw 189, etc. The Il-2 is really a very different machine, other than both of them being low-wing monoplanes with long-ish canopies, single liquid-cooled engines, and the ability to drop bombs. Oh, and both of them can carry bombs in underwing “bays” and have rear gunners. That’s a pretty tiny similarity. The Il-2 was originally designed as a single-seat armored ground attack plane. It was built around heavy cannon armament, a single pilot, and heavy armor from ground fire. That’s really nothing like the formula of the Battle.

Although that brings me to my next point: you have fallen for the same old lies that I’ve seen repeated in numerous sources, that the Battle “utterly lacked armor”. I don’t know where this mnotion originally came from, but it’s been repeated in so many sources that it’s become established “fact” by now. Reality: the Battle was considered heavily armored for the era. Here is an article translated from German discussing armor of various British aircraft, which “only includes the obsolescent Battle due to its unusually heavy armor”, including a diagram of location of all the armor plates, which well-protect the entire rear sector and a good deal of the lower sector from light-caliber fire. It’s not of the same caliber or intent as the heavy armor of the Il-2, but it’s quite heavy for the era (another myth: that the Battle “lacked the armor and self-sealing fuel tanks that were common among its contemporaries”. False. Self-sealing tanks were in their very infancy, and only the very newest British types were fitted with crude self-sealing tanks at the outbreak of the war, and armor was unusual and thin. It wasn’t until after combat experience that they began to hastily add armor to the cockpits and fuel tanks, pending successful production of self-sealing tanks. So you see, the Battle was EXACTLY LIKE its contemporaries, not lacking something that other planes had all adopted by then. The Wellington, Hampden, Whitley, none of them entered the war with self-sealing tanks. No US combat craft had them. Not sure about the Hurricane, but they were a new gadget on Spitfires. I don’t think things were any different with the Germans.

But on the whole I totally agree with you: there was nothing wrong with the Battle, per se. If the British hadn’t been obsessed with the mistaken notion of bombers fighting their way through to the target all alone, the Battle could have been a far more successful machine. If protected by a suitable escort to keep the fighters off of the bombers (and used on lighter battlefield targets instead of heavily defended targets that were more properly the work of more powerful bombers), it could have enjoyed a very different reputation, and be remembered as a useful light bomber and auxiliary aircraft. The Ki-52 and Il-2 were both highly successful in their niches…but you didn’t see the Japanese sending the Ki-51 against heavily-defended dockyards. And you didn’t see them sending the B5N to attack the US fleet without fighter escort…when they did, they were massacred.

….an excellent account. I admin the FB Group ‘Battle of France (RAF 1939 – 1940)’ of which the Battle is a significant contributer of posts…many, many myths of the Battle being eradicated.

My father, Malcolm Wallace Bowen, and Ron Ward were survivors of the mid-air crash between Fairey Battles 1025 and 2066. I found some information about the crash and the 4 fatalities, but nothing about the survivors. Do you have any information about the Battle Mk. 2066 and its crew? I would love to know more about that particular airplane and its crew.

Yours very truly,

Linda (Bowen) Moore

To regret, author of article Nico Braas is not with us anymore, so no way to provide any reply to you

PS My father lived for 12 years after the accident; he was very badly burned, and was in and out of hospital for the first few years after the crash.