The Fairey Rotodyne

The idea of a convertiplane is not new. A combination of a helicopter and a fixed-wing aircraft has been tried several times. However, such a convertiplane not only combines the advantages of both separate types, but also the disadvantages like higher costs, lower speed and range and less capacity! In spite of this a British aircraft manufacturer almost succeeded to make this formula economical feasible.

However, the project failed for political reasons and, most likely, also because of poor company management. The plane involved is the Rotodyne of the late fifties/early sixties, a design from Fairey Aviation Ltd.

How it started…

Preceding the Rotodyne, Fairey already had some experience with this type of design, Already in 1947 Fairey test pilots flew the Gyrodyne. This was a small helicopter fitted with an extra tractor propeller fitted at the end of a short wing stub, The Gyrodyne could start and land as a normal helicopter with the rotor torque compensated by the propeller. During forward flight the rotor could be declutched from the power source and set in autorotation. The propeller served in this case for propulsion. Both propeller and rotor were driven by a single 520 hp Alvis Leonides T air-cooled radial engine buried in the fuselage centre section. Two prototypes of the Gyrodyne were built, carrying the civil registrations G-AIKF and G- AJJP. G-AIKF made its first flight on 7 December 1947. G-AJJP was ready to join the test flight program in March 1948. On 28 June 1948 test pilot Basil Arkel established with G-AIKF a world speed record for rotary-winged aircraft of 200 km/h. Unfortunately, the first Gyrodyne crashed on 17 April 1949 during the preparations for a new 100-km closed circuit record flight killing pilot F.H. Dixon and his flight observer Derek Garroway.

Preceding the Rotodyne, Fairey already had some experience with this type of design, Already in 1947 Fairey test pilots flew the Gyrodyne. This was a small helicopter fitted with an extra tractor propeller fitted at the end of a short wing stub, The Gyrodyne could start and land as a normal helicopter with the rotor torque compensated by the propeller. During forward flight the rotor could be declutched from the power source and set in autorotation. The propeller served in this case for propulsion. Both propeller and rotor were driven by a single 520 hp Alvis Leonides T air-cooled radial engine buried in the fuselage centre section. Two prototypes of the Gyrodyne were built, carrying the civil registrations G-AIKF and G- AJJP. G-AIKF made its first flight on 7 December 1947. G-AJJP was ready to join the test flight program in March 1948. On 28 June 1948 test pilot Basil Arkel established with G-AIKF a world speed record for rotary-winged aircraft of 200 km/h. Unfortunately, the first Gyrodyne crashed on 17 April 1949 during the preparations for a new 100-km closed circuit record flight killing pilot F.H. Dixon and his flight observer Derek Garroway.

By 1953, the remaining second Gyrodyne was extensively rebuilt. It was fitted with a two-stage compressor from a Rolls Royce Merlin providing compressed air for the rotor-tip drives. Fuel-injection at the tips provided further rotor thrust. In fact the Austrian engineer Friedrich von Doblhoff had pioneered on this type of propulsion during the Second World War with the experimental WNF 342 helicopter and it was no coincidence that one of von Doblhoff’s development engineers, Dipl. Ing. August Stepan, was on Fairey’s payroll! Further, the Jet-Gyrodyne as this development was called featured not one but two shaft-driven propellers on the wing stubs. Fitted with the military serial number XD749, it made its first flight in January 1954. It was later for administrative reasons re-serialed as XJ389. By September 1956 it had made 190 transition landings and 140 autorotation landings. The flight experiences gained with the Jet-Gyrodyne were very important for the later Rotodyne! For those who are interested: the Jet-Gyrodyne is presently on display in the RAF Aerospace Museum at Cosford, UK.

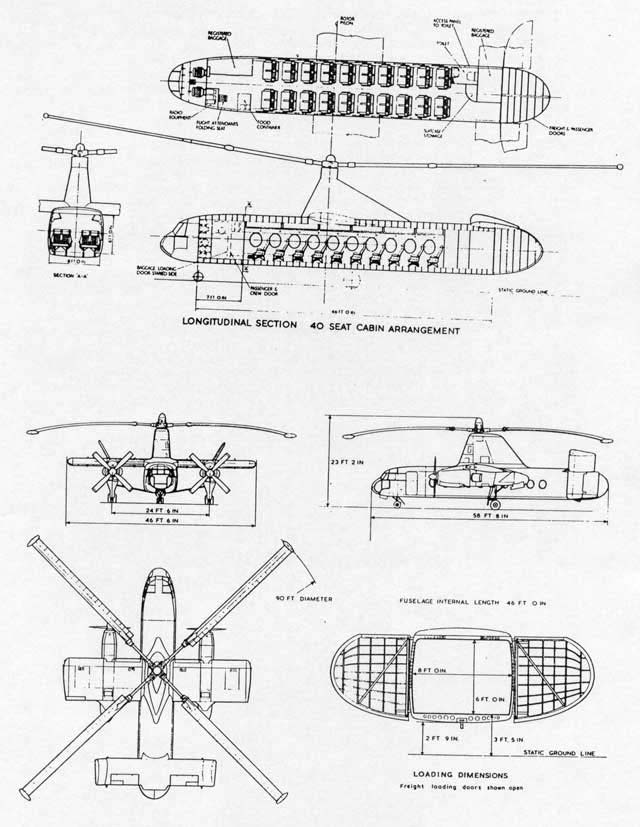

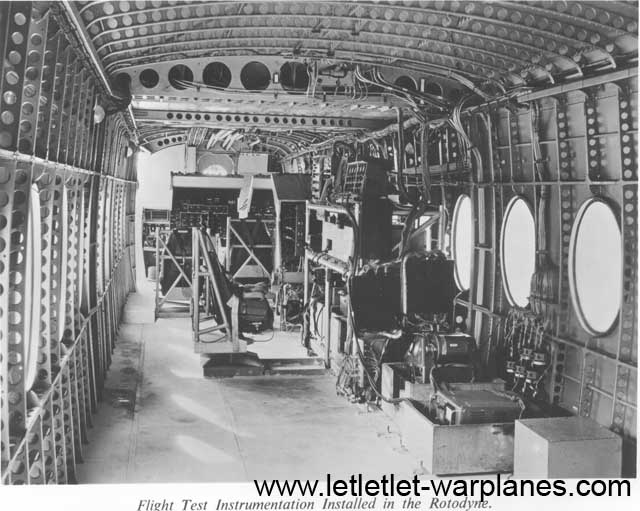

The first illustrations of the Rotodyne were released early fifties by Fairey. They showed a typical combination of a fixed-wing airplane and a helicopter. The Rotodyne design showed a conventional aircraft fuselage with at the rear side a large clam-shell type door that could be opened vertically. The fuselage, fitted with a double rudder, had a capacity for 40 to 50 passengers. Further it showed short plank-like shoulder wings with two engine nacelles housing turboprop engines. So far the ‘aircraft’ part description! Now the helicopter part: centrally on top of the fuselage was a central pylon fitted with a large four-bladed rotor with a diameter of some 27.5 metres. The blades were made of steel. Just as with the Jet-Gyrodyne this rotor was fitted with a jet-drive at each tip. During the start the both turboprops served as compressors to feed air to the rotor tips through a duct system in the wings, rotor head and rotor blades with the propellers in neutral pitch. In the jet-drives compressed air was mixed with kerosene and ignited. So, the rotor turned exclusively on the power of these tip-jets. One of the advantages of this system was the absence of rotor torque which did not have to be compensated for by an extra tail rotor. When the rotor r.p.m. was sufficient, a normal helicopter start was made. Next, when the Rotodyne had gained sufficient altitude, the engine power was slowly transferred to the propellers. At sufficient forward speed the fuel supply to the tip-jets was cut with the rotor revolving further in autorotation. At normal forward flight the wings contributed for 60% of the total lift; the remaining 40% was generated by the rotor blades. For the landing the whole procedure was reversed, a procedure that had been extensively practiced on the Jet-Gyrodyne. The thrust of the tip-drives was 454 kg. Basically the Rotodyne could land on an area as big as two tennis courts.

The first illustrations of the Rotodyne were released early fifties by Fairey. They showed a typical combination of a fixed-wing airplane and a helicopter. The Rotodyne design showed a conventional aircraft fuselage with at the rear side a large clam-shell type door that could be opened vertically. The fuselage, fitted with a double rudder, had a capacity for 40 to 50 passengers. Further it showed short plank-like shoulder wings with two engine nacelles housing turboprop engines. So far the ‘aircraft’ part description! Now the helicopter part: centrally on top of the fuselage was a central pylon fitted with a large four-bladed rotor with a diameter of some 27.5 metres. The blades were made of steel. Just as with the Jet-Gyrodyne this rotor was fitted with a jet-drive at each tip. During the start the both turboprops served as compressors to feed air to the rotor tips through a duct system in the wings, rotor head and rotor blades with the propellers in neutral pitch. In the jet-drives compressed air was mixed with kerosene and ignited. So, the rotor turned exclusively on the power of these tip-jets. One of the advantages of this system was the absence of rotor torque which did not have to be compensated for by an extra tail rotor. When the rotor r.p.m. was sufficient, a normal helicopter start was made. Next, when the Rotodyne had gained sufficient altitude, the engine power was slowly transferred to the propellers. At sufficient forward speed the fuel supply to the tip-jets was cut with the rotor revolving further in autorotation. At normal forward flight the wings contributed for 60% of the total lift; the remaining 40% was generated by the rotor blades. For the landing the whole procedure was reversed, a procedure that had been extensively practiced on the Jet-Gyrodyne. The thrust of the tip-drives was 454 kg. Basically the Rotodyne could land on an area as big as two tennis courts.

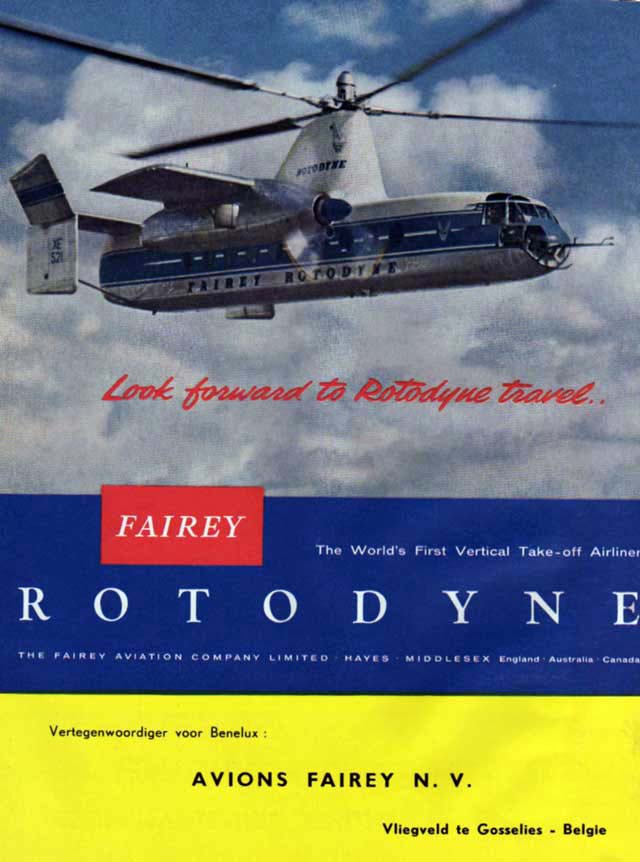

The Ministry of Supply ordered for evaluation trials a prototype, designated as the Rotodyne Y. It was fitted with two Napier Eland turboprop engines. After ground resonance trails indicated severe vibrations in the undercarriage legs, these were placed in a fixed position, strengthened with two extra struts. In this form, it made its first helicopter lift off on 6 November 1957. On this occasion it was flown by RAF test pilots W.R. Gelatly and J.G.P. Morton from the White Waltham airfield near Maidenhead. The first transmission flight from helicopter into autorotation mode and vice-versa took place on 10 April 1958. During this early flight stage, the Rotodyne flew in bare metal colours with only the RAF serial number XE521 on the vertical tail surface. Later, it was sprayed in a very attractive white/silver/Royal blue colour scheme with the name Fairey Rotodyne in large stencilling on the fuselage sides and in smaller form on the rotor pylon. In the summer of 1958 the fixed strutted undercarriage was replaced by its final fully retractable version fitted with extra vibration dampers. The Rotodyne showed its potential very clearly on 5 January 1959 when it set a world speed record in its class by flying a 100 km close-circuit with an average speed of 307 km/h. During this event it was again flown by first-hour test pilots Gelatly and Morton. In June of the same year, it was flown to Le Bourget airport to participate in the Paris air show.

The Ministry of Supply ordered for evaluation trials a prototype, designated as the Rotodyne Y. It was fitted with two Napier Eland turboprop engines. After ground resonance trails indicated severe vibrations in the undercarriage legs, these were placed in a fixed position, strengthened with two extra struts. In this form, it made its first helicopter lift off on 6 November 1957. On this occasion it was flown by RAF test pilots W.R. Gelatly and J.G.P. Morton from the White Waltham airfield near Maidenhead. The first transmission flight from helicopter into autorotation mode and vice-versa took place on 10 April 1958. During this early flight stage, the Rotodyne flew in bare metal colours with only the RAF serial number XE521 on the vertical tail surface. Later, it was sprayed in a very attractive white/silver/Royal blue colour scheme with the name Fairey Rotodyne in large stencilling on the fuselage sides and in smaller form on the rotor pylon. In the summer of 1958 the fixed strutted undercarriage was replaced by its final fully retractable version fitted with extra vibration dampers. The Rotodyne showed its potential very clearly on 5 January 1959 when it set a world speed record in its class by flying a 100 km close-circuit with an average speed of 307 km/h. During this event it was again flown by first-hour test pilots Gelatly and Morton. In June of the same year, it was flown to Le Bourget airport to participate in the Paris air show.

Originally, the Rotodyne was fitted with two short hanging vertical stabilizers connected with an extra strut to the rear fuselage. To improve forward stability during high speed flight it was fitted with two upwards extending extensions which could be placed in an upright and a horizontal position. Even this was not found to be enough and in its final form a third centrally placed vertical stabilizer was added.

Originally, the Rotodyne was fitted with two short hanging vertical stabilizers connected with an extra strut to the rear fuselage. To improve forward stability during high speed flight it was fitted with two upwards extending extensions which could be placed in an upright and a horizontal position. Even this was not found to be enough and in its final form a third centrally placed vertical stabilizer was added.

Although the Rotodyne prototype was built under a military contract, Fairey also aimed at the civil market. After negotiations with various airline companies options were booked by B.E.A. for six final production aircraft followed by additional options by the U.S. New York Airways with a letter of intend for five with option for ten further machines and the Canadian Okanagan Airways with a letter of intend for one plus options for two more. Many other airline companies also showed a strong interest in the Rotodyne. Fairey had also contracted the U.S. Kaman Aircraft Corporation for future license construction. Further the Ministry of Supply had placed an option for 20 Rotodyne Z production models for the Royal Air Force. The Rotodyne Z production model was planned with more powerful Rolls Royce Tyne turboprops of 5250 shaft hp each and an increased wingspan. In this form, the Rotodyne could transport 50 to 65 passengers in the civil version and up to 70 armed soldiers in the military version. B.E A. had already planned a direct flight line from London Central to the city of Amsterdam! Also the Dutch naval air service MLD (Marine Luchtvaartdienst) had shown interest in the Rotodyne for operational use in New Guinea, although contacts were never official. Shortly after the visit of the Rotodyne to the Paris Airshow at Le Bourget it was demonstrated to NATO officers at Versailles.

The sad end…

The Rotodyne in its original prototype form had one disadvantage: it produced in helicopter mode an enormous amount of noise. People witnessing helicopter take offs and landings described it as the sound of a hundred hard working locomotives! For military use, this might have been acceptable, but for civil use from densely populated city centers definitely not. Fairey had already started to experiment with various types of sound mufflers for the jet-drives, but with limited success only. To solve this problem, Fairey wanted from the British government an extra financial guarantee for the development of an effective muffler. Unfortunately the request for this came at a political very inconvenient moment. At the late fifties/beginning of the sixties, the Tory government had decided to make major cuts in the military budgets and that meant no money was made available. This eventually resulted in the cancellation of the Ministry of Supply order. Although this was a major set back for Fairey, there still was a fair chance for the Rotodyne being produced in series.

Worse was the fact that Westland had meanwhile taken over Fairey Aviation Ltd. Westland also had a big transport and passenger helicopter in development (the Westland Westminster). Westland had also taken over Bristol Aeroplane Company who was building at that time the Belvedere twin-engine transport helicopter for the R.A.F.

Poor management during the final merging of these companies within Westland and wrongly chosen priorities were retrospectively most likely the main reasons why all work on the production Rotodyne Z never materialized. Westland was unable (or unwilling) to give its costumers which had already placed orders and options a guarantee for a timely supply after the initial Ministry of Supply was order canceled and it did not come as a great surprise when B.E.A., New York Airways and Okanegan withdraw their orders. The Rotodyne was officially canceled in February 1962…

Post-scriptum…

All we can say afterwards is that Westland most likely could have made the Rotodyne into a commercial success at that time. The Rotodyne was unique in its kind and had no competition at all from other types. Further, its load capacity was far beyond anything possible with the helicopter from that time period. With the capacity of up to 70 passengers the production Rotodyne Z could carry more passengers than the Fokker F-27 Friendship which was then the most successful short/medium range twin-engine passenger plane. The F-27 could carry only 44 passengers and still needed a runway!! However, there was a penalty for VTOL operation: it required precious amounts of fuel and that meant it could never be really competitive when compared with a fixed-wing aircraft. This would not have been too restrictive, since the Rotodyne could also operate from normal runways making starts and landing with the helicopter blades in autorotation. This would have been particularly useful for the military version since it made starts possible at overload conditions. With most of its fuel burned at its arrival it could make at forward battlefield locations (and that was where it was to be used for!) a straightforward helicopter landing. As usual for such autogiro-starts take-off distance would have been short!

All we can say afterwards is that Westland most likely could have made the Rotodyne into a commercial success at that time. The Rotodyne was unique in its kind and had no competition at all from other types. Further, its load capacity was far beyond anything possible with the helicopter from that time period. With the capacity of up to 70 passengers the production Rotodyne Z could carry more passengers than the Fokker F-27 Friendship which was then the most successful short/medium range twin-engine passenger plane. The F-27 could carry only 44 passengers and still needed a runway!! However, there was a penalty for VTOL operation: it required precious amounts of fuel and that meant it could never be really competitive when compared with a fixed-wing aircraft. This would not have been too restrictive, since the Rotodyne could also operate from normal runways making starts and landing with the helicopter blades in autorotation. This would have been particularly useful for the military version since it made starts possible at overload conditions. With most of its fuel burned at its arrival it could make at forward battlefield locations (and that was where it was to be used for!) a straightforward helicopter landing. As usual for such autogiro-starts take-off distance would have been short!

Would the Rotodyne have been pursued and would it have been a success, other aircraft manufacturers might have followed with similar competing designs and short-range transport as we know it at present MIGHT have been totally different!! With the production Rotodyne operational in the sixties, it would have been undoubtedly developed further. Even a braking system to stop the rotor during flight and continue flying as an X-plane would have been possible without the need for Sikorsky in the late eighties to ‘discover’ this type with their RSRA( which also never became a success; it never flew with its planned X-wing!). And at lighter and stronger manufacturing materials as used later, cost-efficiency would only have increased!

Would the Rotodyne have been pursued and would it have been a success, other aircraft manufacturers might have followed with similar competing designs and short-range transport as we know it at present MIGHT have been totally different!! With the production Rotodyne operational in the sixties, it would have been undoubtedly developed further. Even a braking system to stop the rotor during flight and continue flying as an X-plane would have been possible without the need for Sikorsky in the late eighties to ‘discover’ this type with their RSRA( which also never became a success; it never flew with its planned X-wing!). And at lighter and stronger manufacturing materials as used later, cost-efficiency would only have increased!

Retrospectively, we can only say the aircraft industry of the United Kingdom missed an unique opportunity!!

| Technical details: | Rotodyne Y | Rotodyne Z |

| Engine: | 2 Napier Eland H.E1-3 2 Rolls Royce Tyne | |

| Engine output: | 3000 shaft hp each | 5250 shaft hp each |

| Wingspan: | 14.17 m | 17.22 m |

| Length: | 17.88 m | 19.67 m |

| Height: | 6.76 m | 7.06 m |

| Rotor diameter: | 27.43 m | 31.72 m |

| All-up weight: | 14,968 kg | 22.700 kg |

| Maximum speed: | 307 km/h | >320 km/h |

| Range: | max. 724 km | 1180 km |

| Accommodation: | 40 passengers | max. 70 passengers |

How the Rotodyne would score today:

It is interesting to compare the Rotodyne Z capabilities and performances with its modern ‘counterparts’ the Boeing-Vertol Chinook and the Bell-Boeing V-22 Osprey.

|

Fairey Rotodyne Z |

Boeing Helicopters CH-47D Chinook |

Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey |

|

|

Engine power |

2 x 5250 hp |

2 x 4378 hp |

2 x 6150 hp |

|

All-up weight |

22,700 kg |

24,494 kg |

23,000 kg |

|

Max. speed |

320+ km/h |

298 km/h |

550 km/h |

|

Range |

1180 km |

1190 km |

3892 km |

|

Accommodation (military) |

70 passengers |

45 passengers |

24 passengers |

As we may conclude from the figures in the table, the final production Rotodyne Z would have been definitely competitive if pursued by Westland. And that applies both to military and civil market. It is particularly surprising to see that the Rotodyne from more than 35 years ago has a much larger passenger capacity than both Chinook and Osprey of today at roughly the same weight! Of course the Osprey is far superior in speed and range, but it has only a third of the passenger capacity of the Rotodyne and the tilt-wing mechanism is much more complicated and maintenance-unfriendly than the compressed-air system of the Rotodyne. As known, it took a very long ‘gestation’ period before the Osprey was fully operational at U.S. Marine forces!

Tips for the model builders:

In the early sixties Airfix released a 1/72 scale model kit of the Rotodyne Y. It was well detailed with in total 101 parts. The finished model showed at least a rudimentary cockpit interior and clamshell rear doors that could be really opened and closed. For that time it was reasonably accurate with a fairly good fit of all parts. Airfix has re-released this kit in the early nineties and with some luck it still can be obtained at specialized hobby shops. Now Airfix has gone bankrupt, a new release of the Rotodyne is far from certain and we can only hope on a future new release. The Airfix Rotodyne could be finished in its original colours silver, white and royal blue as the XE 521 in Fairey livery.

In the early sixties Airfix released a 1/72 scale model kit of the Rotodyne Y. It was well detailed with in total 101 parts. The finished model showed at least a rudimentary cockpit interior and clamshell rear doors that could be really opened and closed. For that time it was reasonably accurate with a fairly good fit of all parts. Airfix has re-released this kit in the early nineties and with some luck it still can be obtained at specialized hobby shops. Now Airfix has gone bankrupt, a new release of the Rotodyne is far from certain and we can only hope on a future new release. The Airfix Rotodyne could be finished in its original colours silver, white and royal blue as the XE 521 in Fairey livery.

Nico Braas

References:

Nico Braas, De Fairey Rotodyne, Luchtvaartkennis Vol.37, June 1988

Patrick McDonnell, Requiem for the Rotodyne, Aeroplane Monthly, Jan. 2000

H.A. Taylor, Fairey aircraft since 1915, Putnam-London (1974)

I cant believe they built the ridicously expensive, complicated and dangerous Osprey when they had this type aircraft available.

.

.

.

Have photos of FaireyRotodyne from 1970-71

.

Interested, let me know

.

.

.

Hi,

I am interested in all I can get from the Rotodyne. Pictures, data, informations, tech details, Even sound recordings!

I have no size limits on my email, so please send me whatever you’d like to share. Thank you in advance.

Franky

Thank you for your kind reply and interest in this material. If you have seen Terms (I guess not as well nobody read it) you will realize that we are not dedicated as archive material support place. For high quality material you should contact some archive.

Regards 😛

6/20/2012 – I’ll soon be making a Flight Simulator FSX Video of this Fairey Rotordyne, should be done with it by the end of July or sooner , be a long video of 45 minutes or more in detail ! stay tuned to my YOU TUBE web site / http://www.youtube.com/user/IFLYWINGS?feature=mhee – JetRanger !

I have a number of the original test flight photographs of the “Rotodyne”. I will be hanging on to them but anybody wants copies of them,

I may be able to arrange that. For a long time, I have been thinking of the “Rotodyne” concept but with a “Spine” instead of a fuselage connecting the cockpit, wings, rotor pylon and tail-plane and having the capacity to have the largest shipping container underneath. The functions would be

quickly interchangeable in between a passenger container and pre-loaded cargo containers, and for each a reduced drag after body underneath

the tail-plane would be used. I would like to hear other people’s comments on this idea.

I am the author of Fairey Rotodyne, History Press 2009. I also flew with Rotodyne. It is implied in your statement that Westland did not pursue the Rotodyne with any enthusiasm . This is unfair and untrue! Westland was responsible for almost half its flying life. And discarded its own project Westminster o do so.They had more sense than to continue as a private venture working with British European Airways. on a fixed budget.

I have always said that to cancel Rotodyne was not necessarily wrong. What was unforgivable was scrapping the prototype and losing the data. No one has ever owned up to this.

I worked for Fairey but I would always claim that Westland worked hard to make Rotodyne a success

Let’s come off the popular conspiracy theory, and heaven forbid that there may have been any government incompetence or lash of drive.

David Gibbings MBE